Continue reading “Such Coup. Many Unconstitutional. So Thwart. [5 Feb — ongoing]”

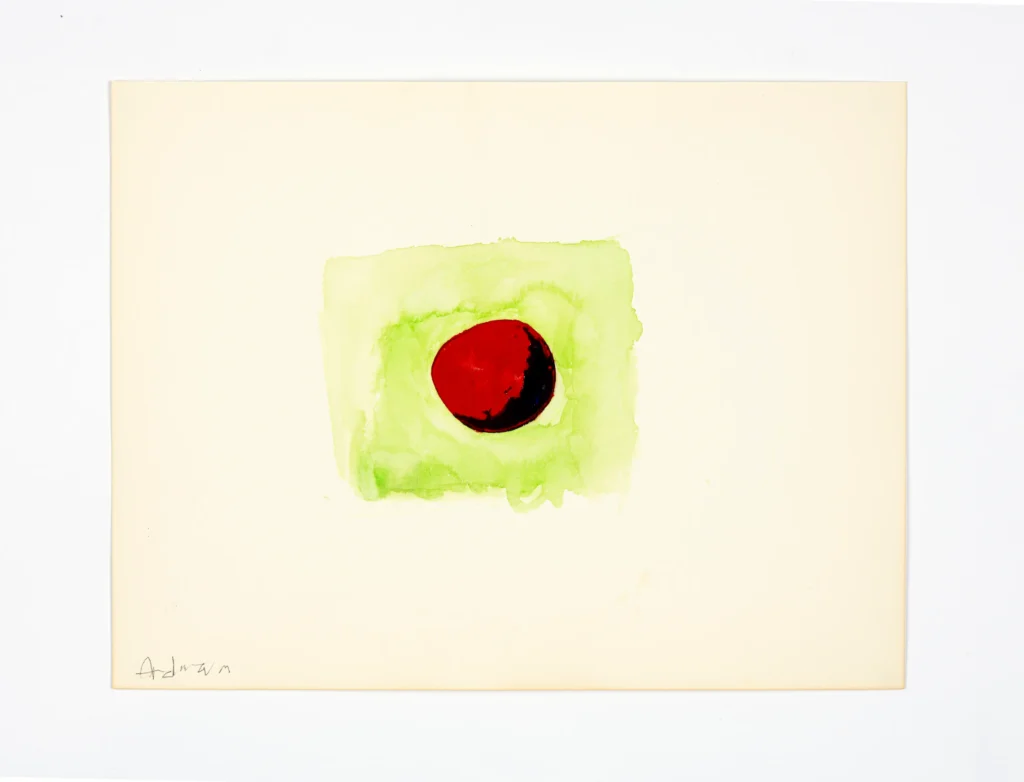

Etel Adnan’s Language of Painting

First things first, Galerie Lelong’s exhibition of Etel Adnan’s works on paper is on view for two more days, so get going.

I’ve been listening to Kaelen Wilson-Goldie’s interview about Adnan on Bulaq, the podcast of Ursula Lindsey and M Lynx Qualey (ArabLit editor), and right around 24:00 Wilson-Goldie turns the question back to her book-centric hosts, to ask what they think the complicatedly multilingual Adnan meant by her statement that she “painted in Arabic.”

I would love to know more of the context in which she first said that. Wilson-Goldie, Lindsey, and Qualey talk about Adnan’s shifts from writing in French to English as her perspective and contact with French and US colonialism changed. But also how her return to Lebanon in the 1970s included a mutual embrace with the new Arabic poetry communities of the day.

I can absolutely see the appeal of a painting language that did not carry with it the political baggage, while also making an affirmative assertion of solidarity. Or maybe that characterizing painting as a language separate from the ones she used for writing helped justify it, or at least made it make sense within/alongside her multi-faceted, text-based practice. Or maybe it just gave her the psychological and linguistic space she needed for a personal expression. I’m trying to think of many novelist/poets who were also recognized for their painting, but ngl, my head is not primed for unfettered rumination on poetry today [noon]. Wonder why.

In any case, I feel like I have to rethink my understanding of Adnan’s work a bit precisely because I’d always read it—or seen it presented— as being an Arabic-inflected modernism being subsumed into the larger modernist project. And I have to consider that that could be just how it looks from my perspective in the distended belly of that empire.

[listened to the end of the podcast update: OK, so Adnan had various complex takes on what it meant, and why she did not, in fact, learn Arabic. And I wonder what it means that this was the language she analogized to her painting.]

Etel Adnan on Paper: 1961-2021 runs through Apr 5, 2025 [galerielelong]

Bulaq | Etel Adnan: ‘I write what I see, paint what I am’ [sowt/bulaq]

Whoops, missed Etel Adnan centenary show at White Cube [whitecube]

ArtSeen | Ann McCoy on Etel Adnan [brooklynrail]

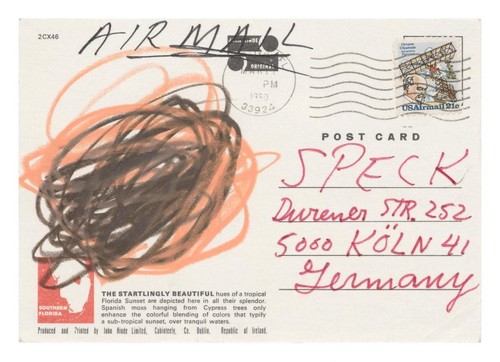

Heading To Bassano, Wish You Were Here

It’s the little differences. Where Marcel Duchamp’s letters to his collector friend Katherine Dreier are all, “shipping is $34, please send me $34,” Cy Twombly’s letters to his collector friend Reiner Speck are like, “we await you in the summer castle.” I have read the Twombly correspondence with noted urologist and Proust expert Herr Dr. Reiner Speck in the catalogue for Maison d’Art’s current exhibition, and here’s the expanded tl;dr:

Continue reading “Heading To Bassano, Wish You Were Here”Ellsworth & Kelly & Lorenzetti & Kubrick

I was listening to a recording of Ellsworth Kelly’s 1999 Elson Lecture at the National Gallery of Art, and I have some questions. Some could probably be answered by a video of the lecture—more of a conversation, with curator Marla Prather—or with a review of Kelly literature I don’t have.

Continue reading “Ellsworth & Kelly & Lorenzetti & Kubrick”A Use Of Opulence Comes As Some Surprise

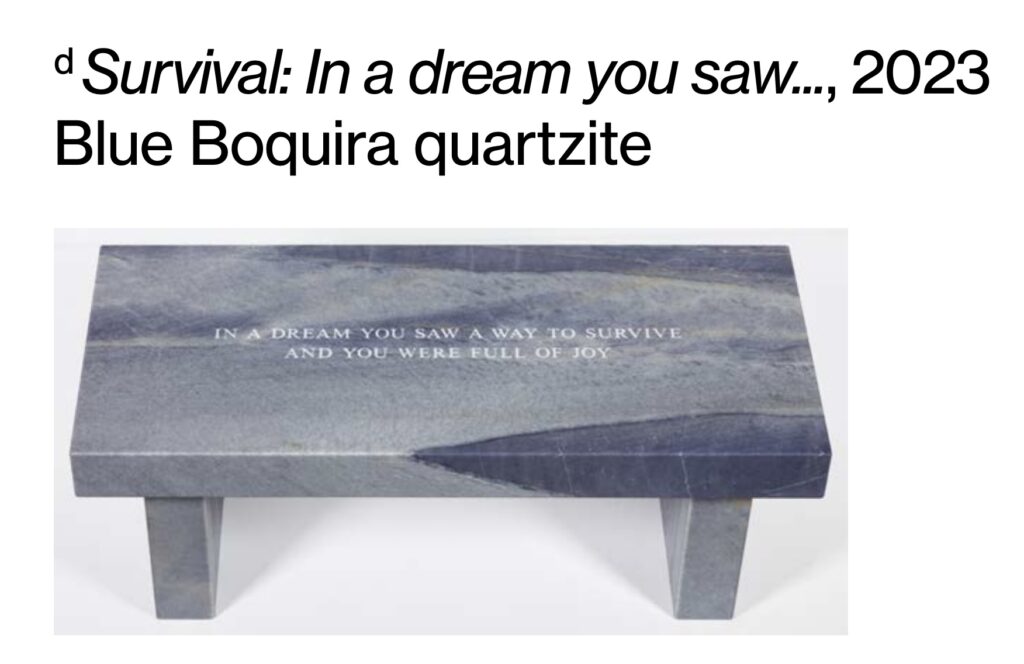

I was not prepared to be taken out a Jenny Holzer exhibition, especially since her most recent show at the Guggenheim seemed so lost. But that was then and there, and this is here—in DC, at Glenstone—and now—in the midst of a fascist crime spree by and against the government.

It was not the merch in the tiny book nook. It was not the entire gallery of redaction paintings—enlarged, oil-on-linen facsimiles of damning documents of the torture and atrocities of Bush’s Iraq war—though I really do wish this country would not give Holzer quite so much content to work with. Turns out abuse of power comes as no surprise because it happens over and over and over.

It was the next gallery of the private museum sanctuary, with the large window onto an artfully crafted vista, where Holzer crashed a tsunami of opulence over my unsuspecting head. It was all benches and paintings, not an LED ticker or a bumper sticker in sight. The benches in Blue sodalite. Bulgari Blue marble. Blue Boquira quartzite. Persian travertine and Silver Wave marble. Paintings large and small, single and in rows, cinnabar and lacquer finishes covered in copper and gold leaf, glowing in the morning sun. The extravagance of Holzer’s materials was so relentless, it was wretched. The polish, the weight, the preciousness, the hand, the logistics, the overpowering beauty impossible to ignore.

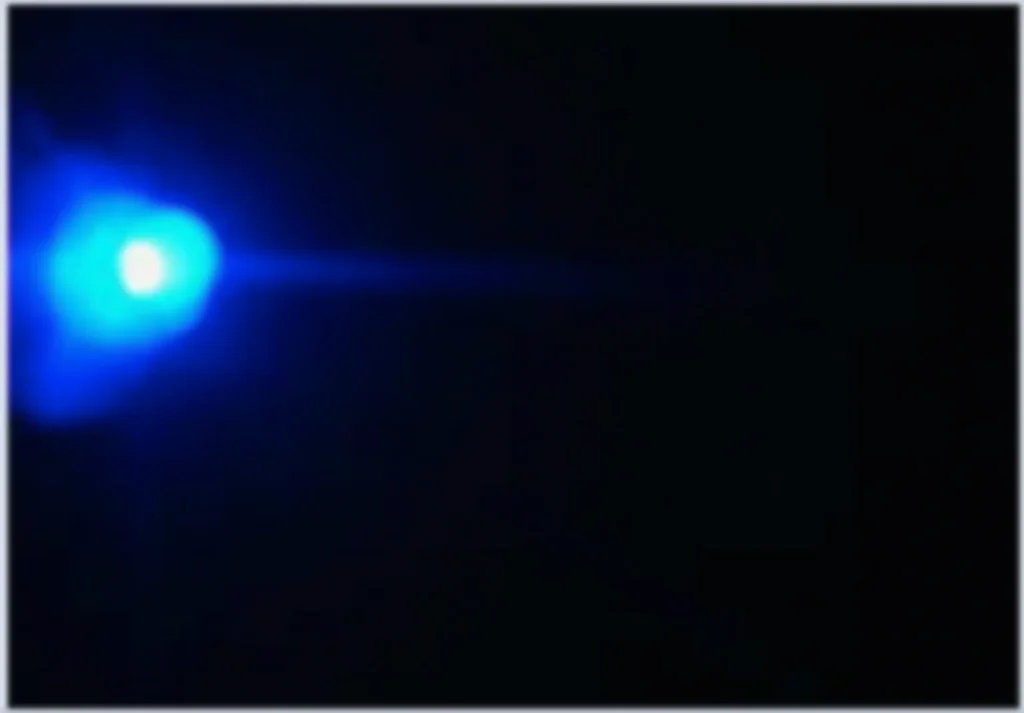

David Hammons Lights

How has there not been more Concerto in Black and Blue content floating around? Do people not go to Hauser & Wirth LA anymore? Is the glow of people recording themselves on their phones ruining it? David Hammons has restaged his epic 2002-3 work in LA. It’s on til June. So grab a little flashlight and become the artwork.

Meanwhile, Ursula has a great essay by legendary filmmaker, gallerist and Hammons whisperer Linda Goode Bryant, who filmed the opening night of Concerto in Black and Blue at the vast NYC outpost of Ace Gallery:

He allowed me to be inside for the opening, to make a short film of what happened inside. And what people didn’t know is that David was actually in there himself that night. I only knew where he was because I had a microphone on him. But he was otherwise totally invisible, moving around among everyone else, watching what they did and what they made, present and at the same time absent.

LGB talks incisively about walking and seeing with the artist, and getting hints of how he sees and works. It confirms my theory/suspicion/last-ditch hope that we are in fact living in David Hammons’ world, and often just don’t realize it.

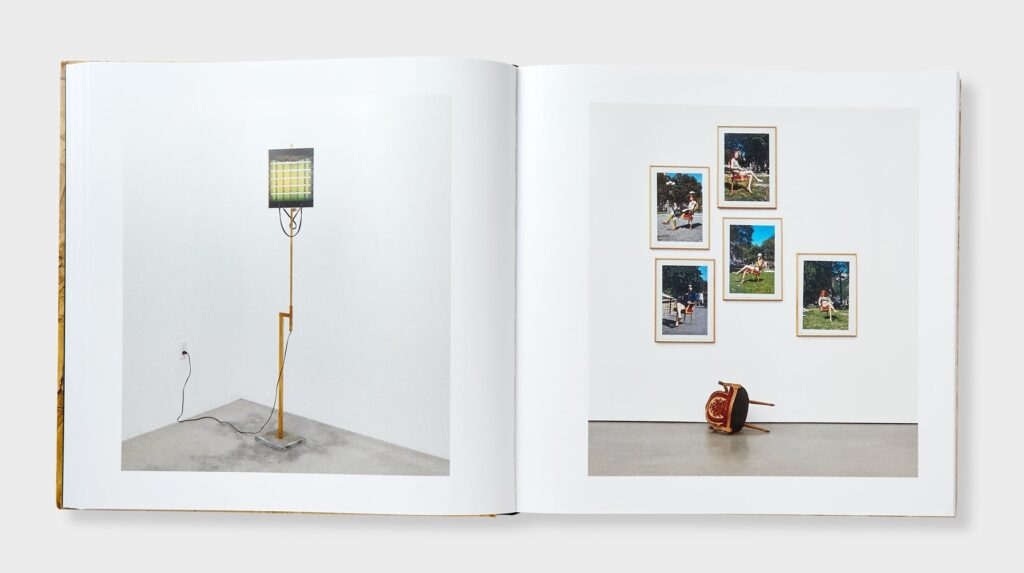

Meanwhile, the book finally documenting Hammons’ sprawling 2019 show at H&W LA is out now, not in May, which means the lamp with the Flavin X Sotheby’s shopping bag lampshade I had to scavenge screenshots in the backgrounds of peoples’ youtube videos like a dog to see is now beautifully photographed on its own.

A Walker in The City | Linda Goode Bryant [hauserwirth/ursula]

David Hammons, Concerto In Black And Blue, 18 Feb – 1 June 2025 [hauserwirth la]

untitled_picksimg_large-6.jpg, 2025 [greg.org]

Previously, related: Untitled (unnamed.jpg), 2019

Previously, related jpg constraint, alternate naming convention: Untitled (300 x 404); Untitled (290 x 404)

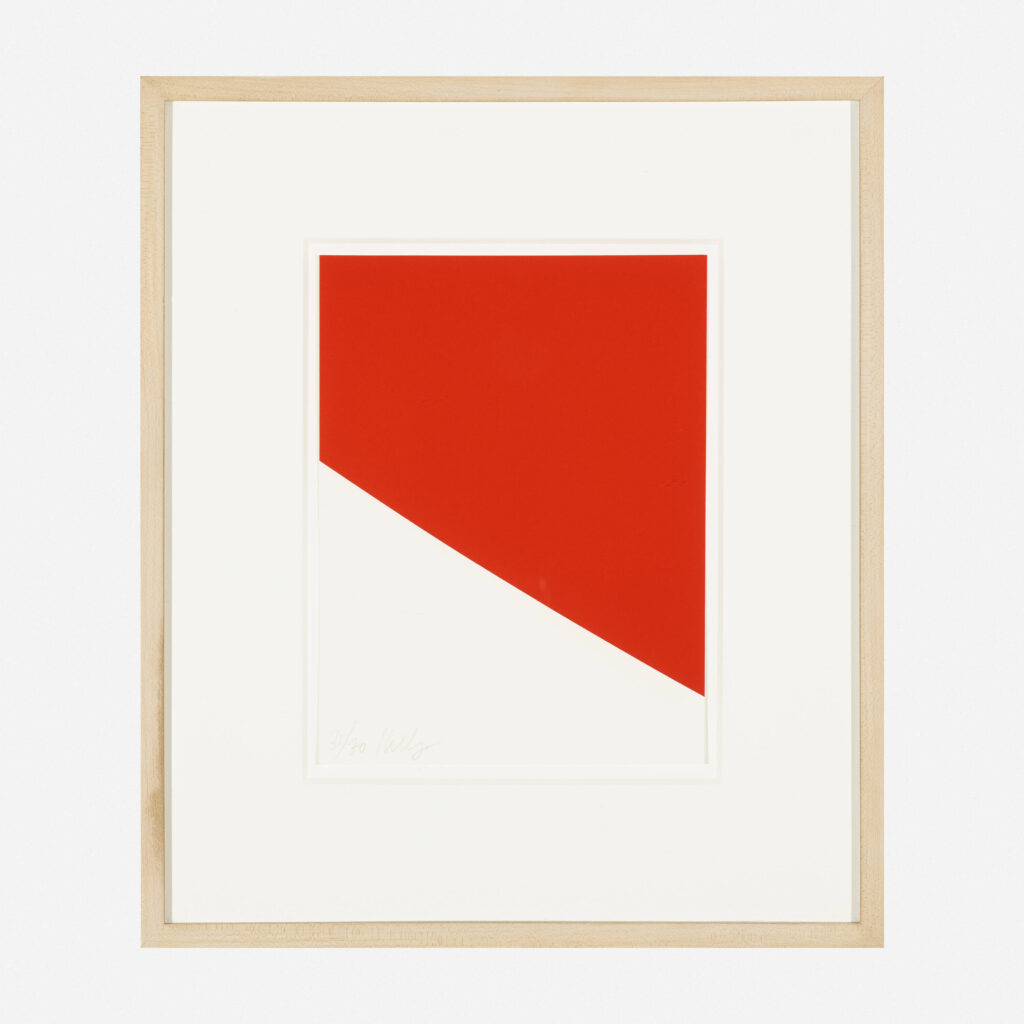

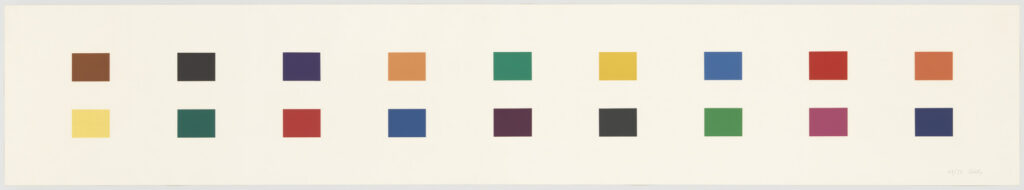

Ellsworth Kelly Extra Small

While poking around the Gemini G.E.L. CR, I was surprised to find that River II (2005), one of Ellsworth Kelly’s superlong prints, was also his second to last print made with Gemini.

I’ll have to check the Kelly prints catalogue raisonné for details—the second edition was published in 2012, but Kelly sure seemed booked and busy right up to the end in 2015.

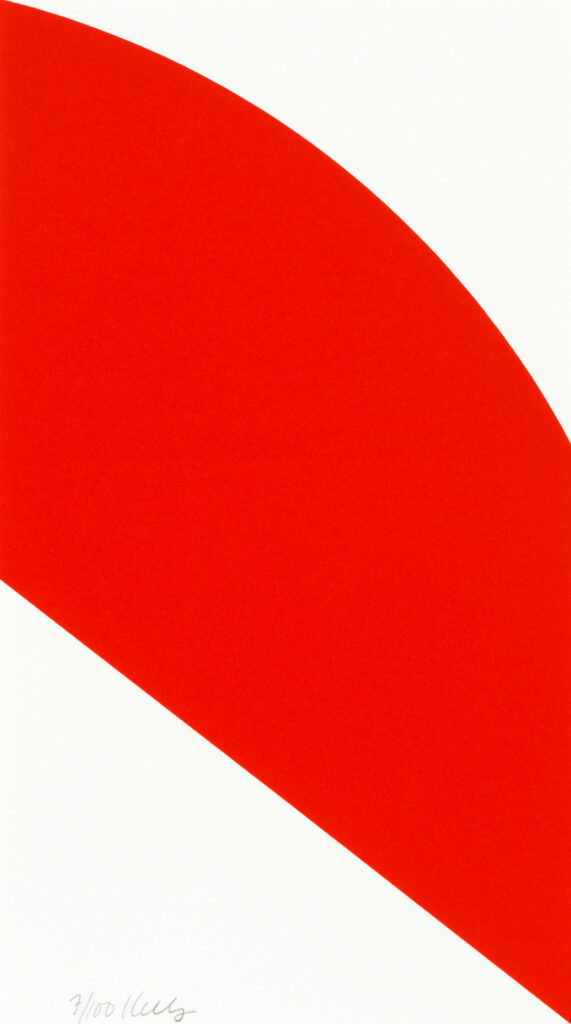

It’s also a surprise because the last print he made with Gemini was maybe his smallest ever. Red Curve (2006) is a single color lithograph, cropped so the shape goes right to the edges and the corners of the 12 x 6 3/4 inch sheet.

Red Curve was published for Kelly’s show at the Serpentine Gallery, a cheap, unframed edition of 100. I feel like it was easily under GBP1000, and at the time, it didn’t even seem real somehow. Now it is fascinating and formally intriguing, especially after the other full-bleed prints he’d just made, that resonate between print and object. Also it’s utterly adorable.

[OK, close to the smallest but not the last: Blue Gray Green Red (2008) was part of the Gemini-organized Artists for Obama portfolio. Here they both are installed at Joni Weyl in 2019.]

later this afternoon update: I went through the CR, published in 2012, but it does end in 2008. I feel like if there were more prints coming, they could have fit them in. So what seems like the last last print for Kelly was a large (48 x 130 in.) version of Blue Gray Green Red. He went big, then he went home.

Rago in 2021

The only smaller edition, though, might be Red Curve (1999), which he made for Parkett, which is 10 x 7 in. And for the 1973 Works By Artists in The New York Collection for Stockholm portfolio, Kelly made an untitled black on white screenprint that is 12 x 9 in. And while there are a couple of similarly sized Concorde etchings in the early 1980s, they’re on traditional, larger sheets.]

Rather than delve into why Kelly stopped, or what the very last prints mean, Richard Axsom, the prints CR editor, looked at what was there: a complete, ambitious, and exceptional project, and said, “River is a great summa to Kelly’s prints.”

Ellsworth Kelly Extra Long

They’re hard to fit on my walls, but Ellsworth Kelly’s superlong prints are permanently installed in my heart.

Continue reading “Ellsworth Kelly Extra Long”946-3 Is The New 724-4

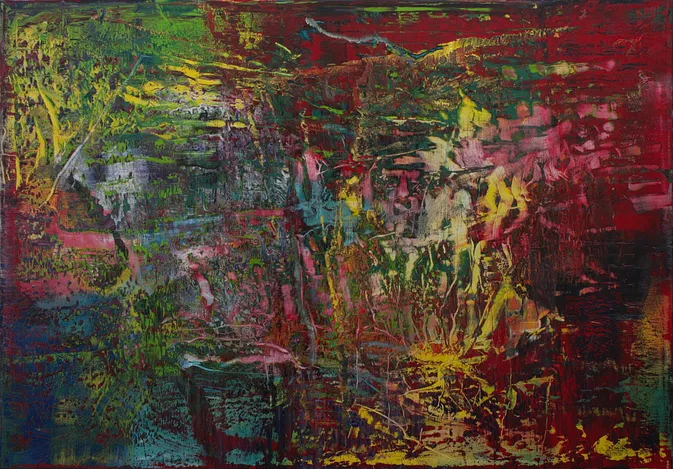

Once every 36 years, a new Gerhard Richter squeegee painting comes along that changes everything. For a long time it was (CR 724-4) (1990), which went on to become at least eleven editions, two artist books, four tapestries, a Facsimile Object, all the Strip paintings, and a movie. (CR 724-4) has been in fourteen museum exhibitions, including all the venues for Richter’s biggest retrospectives at MoMA and Tate Modern, and his COVID-shortened show at the Met.

Now there is (CR 946-3), a 2016 painting that’s already been exhibited six times, including Richter’s last show at Marian Goodman in 2020, and his Foundation’s extended loan to the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, where it’s on view through at least 2026.

Continue reading “946-3 Is The New 724-4”“Hey We Got A Computer! Oh No, We Had A Fraud.”

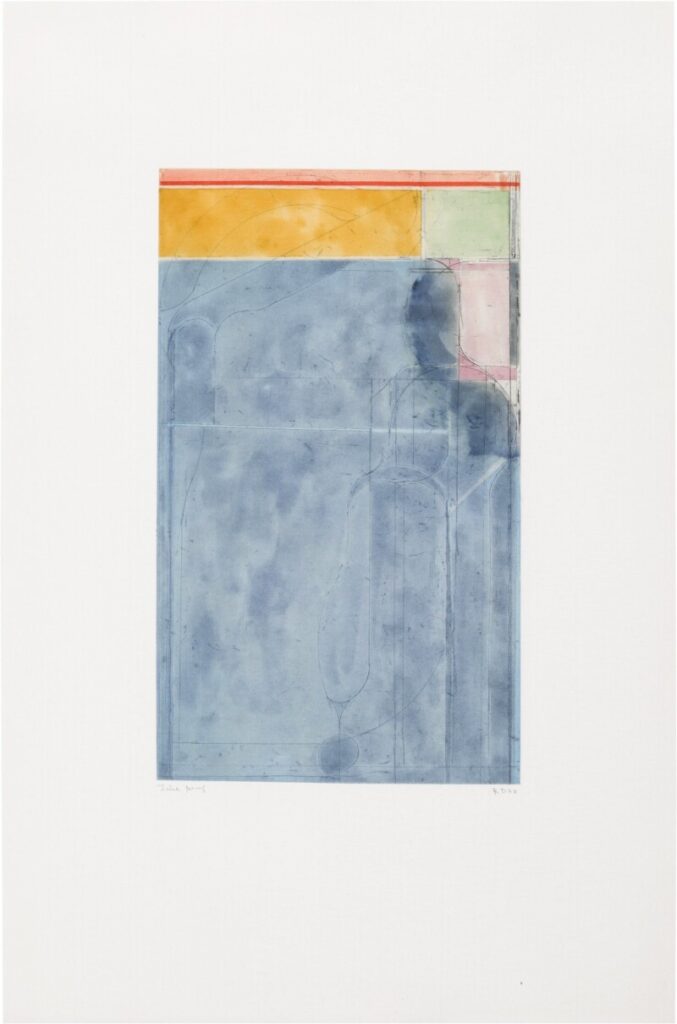

The Spring 1984 newsletter for Crown Point Press [pdf] was notable not just because it was the first in two years. Or because they reflected on their 20th years of enabling contemporary artists to engage with intaglio. Or because they announced their principled expansion into woodblock prints through a collab with master artisans in Japan. Or because they launched their artist-designed silk lingerie collection, which, well. Or because they got a computer, and a new sales director. Actually, let’s stop there and have CPP director Kathan Brown expand on that:

One thing (totally unexpected) the computer has done for us is uncover fraudulent activity perpetrated by our former Sales Representative, Thomas Way. We have a warrant out for his arrest in connection with the theft of many prints. It appears now that he even took home some rejected prints during projects before the printers had a chance to destroy them. These were Diebenkorn’s and the RD signature was easy to forge-one print that we have recovered was even hand-colored (not by Diebenkorn)! Way apparently had a side business going the whole time he worked for us. If you bought anything from him personally, or have any other information, please call.

So wow, while it seems slightly wild to put the guy on blast like that, I guess that’s how print market justice worked in the 80s? Brown’s letter to the editors of Print Collector’s Newsletter ran in the May-June 1984 issue, and contained more details of the caper and the hot, forged prints:

Continue reading ““Hey We Got A Computer! Oh No, We Had A Fraud.””Lingerie & The John Cage Kimono

Is it really chance operations if a seemingly tangential Google search leads me to The John Cage Kimono?? From the Crown Point Press Archive, a gift to the de Young and/or Legion of Honor Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco?

And then an immediate follow-on search turns up the Crown Point Press Spring 1984 newsletter [pdf] which, the contemporary editions drama! I’ll get to the computers and fraud later, but first the “lingerie business”:

Continue reading “Lingerie & The John Cage Kimono”Torn From Today’s Headlines

![a robert rauschenberg screenprint of a collage made of clippings from newspapers in 1969, includes [clockwise from top left] a photo of cars stranded in the snow; a white woman in a miniskirt with a longer skirt drawn over her; a comet; ted kennedy, some racist judge nixon tried to put on the supreme court who eventually got voted down because twelve republicans still had enough conscience left to be shamed over unalloyed white supremacy, can you even imagine? anyway, several articles and photos of gm assembly lines and the threat of robots and depleted pensions; a chevron tanker truck overturned on a freeway; a hand holding a case of birth control pills; a sideshow entrance with the world's largest rats; a coal mining ship and a truck being craned onto a ship; more assembly line; and a ship docking on the hudson pier. from the 26-print portfolio known as Features from Currents, being sold at Wright 20 in apr 2025](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rauschenberg_currents_portfolio-wright20-202504-283-1001x1024.jpg)

Though Our Most Important Art Historians disparage the practice, I could not resist zooming in to read the specific newspaper clippings that Robert Rauschenberg included in just one his 26 Currents prints. Honestly, I did not expect them to hit so hard, one after the other:

The threat of robots taking union jobs

The threat of executives taking union pensions

Gas tanker overturned on a freeway causing mayhem

WORLD’S LARGEST RATS

Birth control

Woman’s outfit-shaming

A problematic Kennedy

A criminal president’s supreme court nominee being exposed as a mediocre southerner whose only firm conviction is white supremacy, getting defended by an unperturbedly anti-semitic republican senator saying, “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance? We can’t have all Brandeises, Frankfurters and Cardozos.”

Even the auction itself, a couple of loosies being stripped and sold off piecemeal, feels topical: people don’t buy 26-print portfolios these days anymore than they read newspapers. And yet the politics and the challenges remain the same.

3 Apr 2025, Lot 283: Robert Rauschenberg, from the [Features from] Currents Portfolio, est. $1,000-1,500 [wright20]

Related: Features from Currents, 1970; Surfaces from Currents, 1970 [moma]

The Knowledge of Tree

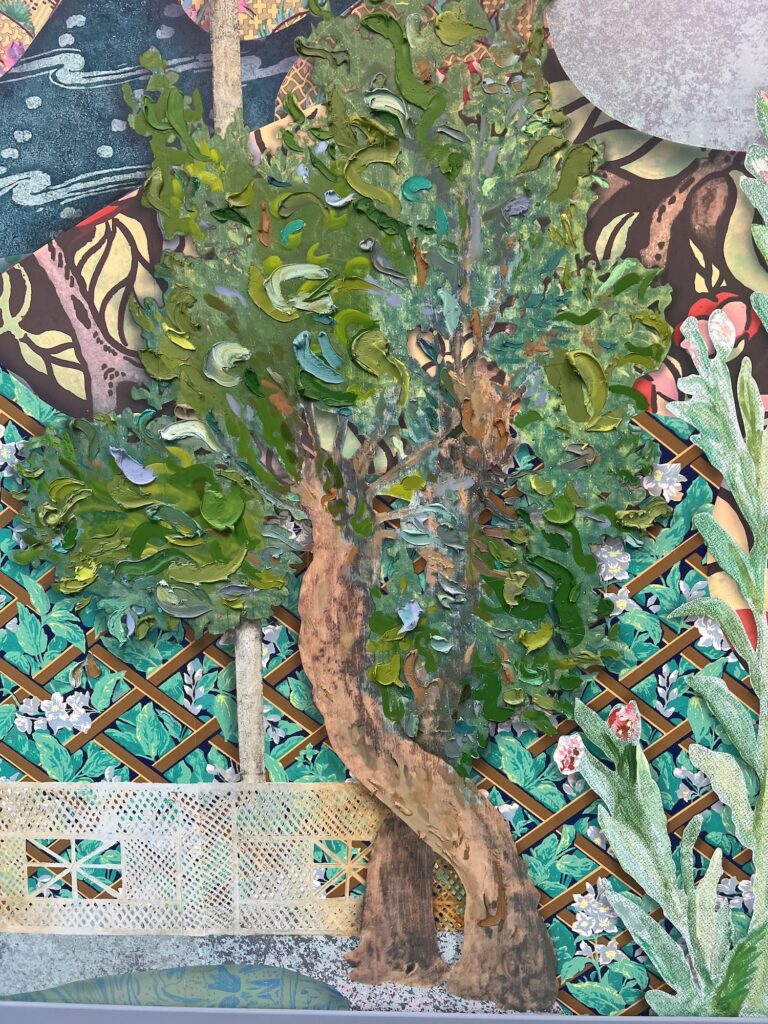

I kept catching myself being attracted to the thick impasto schmears of paint in Laura Owens’ show at Matthew Marks. There was one metallic gold paint object—some of them almost seem to substantial to call them brushstrokes—that sat atop a seam in the panels of the main room, and yes, it turns out she kept working on it after it was installed.

So this tree in the center of the main room felt like the centerpiece, the bravura moment in an already almost unfathomably impressive painting installation.

But even the instant after I took the photo above, I realized that the tree next to it is just as impressive and alluring; it just did it by not standing out [literally]. Should I retake a picture of them together? The combination of silkscreen and painting, the composition, the visual layering—the actual layering? How does this even work? There’s fluidity, or viscosity, on one hand, and precision and control on the other, but fluency all around.

I’m barely able to process the experience of seeing Owens’ show once; but I keep wondering what the experience of making it was like, and the experience of conceiving it, and marveling at it at every turn.

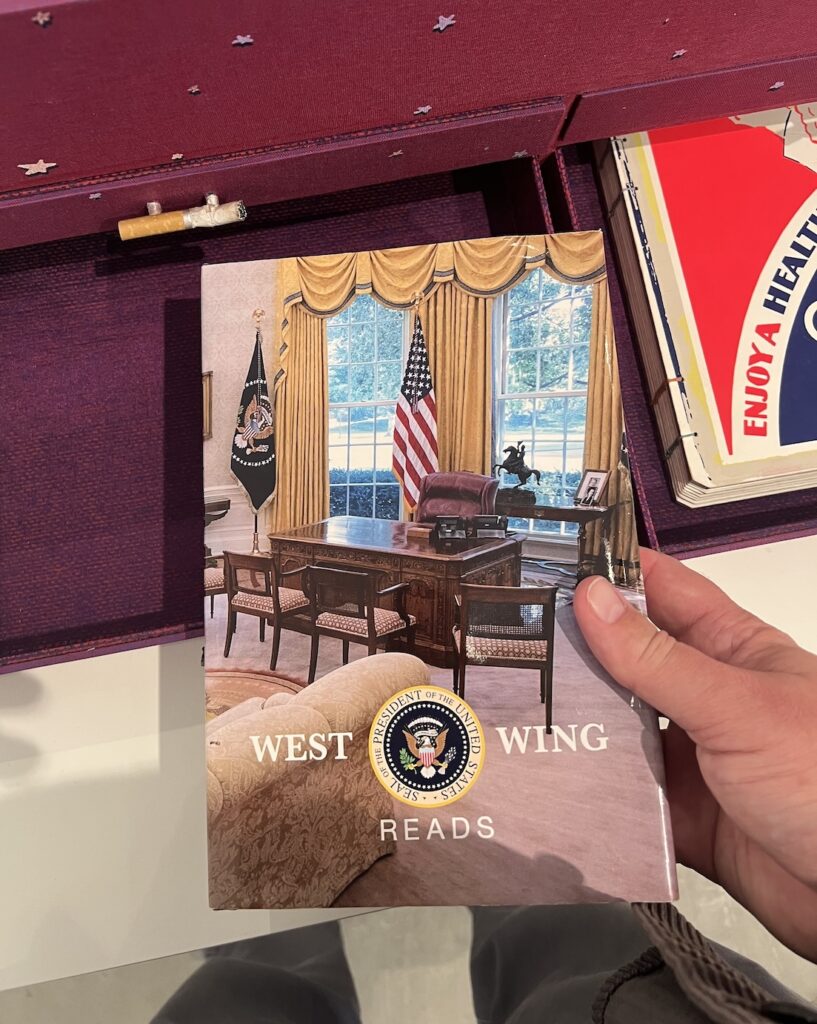

[It’s a contrast, in a way, with the artist books in their cabinets next door. Every single one felt like an understandable achievement, but it was possible to grasp the reality of their creation, even the mindblowing ones that were drawn by hand in unique editions. What is hard to grasp is the scope of her overall book practice. Even as someone who makes art objects that are books, it sometimes feels like she’s inventing entire new genres. Her 2019 work, West Wing Reads, for example, a scraping or compilation of right-wing news reports during the Trump presidency, was like a slab of malevolent poison in the innocuous form of a banal airport book. The sequel, which is probably being written by AI as I type this, will be even worse.]

Overpainted, Underhyped

Just WTEFAF? Look at this thing.

Let’s stipulate that it is wild that objects survive for hundreds of years, so each one is a little miracle and marvel of its own. But how did this painting come to be, and how did it come to be in Simon Dickinson‘s booth at TEFAF?

At least I can understand how it showed up in front of me: artnet published a TEFAF highlights roundup, which pwlanier posted on tumblr. Tracking it down beyond that only turns up Dickinson’s press release, some instagram shoutouts, and a brief youtube video of Dickinson son Milo discussing the painting.

Basically, it’s a 17th century Dutch seascape painted over a slightly earlier 17th century Dutch portrait of an unidentified man. As artnet reports, the head was only uncovered after a recent cleaning. So for centuries, the painting had looked like a regular, little seascape, c. 1685-1690, which Dickinson attributes to Ludolf Backhuysen, Amsterdam’s leading marine painter at the time.

The cleaning also apparently revealed the seascape painter’s meticulous, intentional preservation of the portrait—which Dickinson attributes to Isaack Luttichuys, with a date of 1655-1660.

I do not have the connoisseurial chops to raise any issue with the Dickinsons’ attributions; for what it’s worth—nothing—they look solid to me. Backhuysen was already a leading painter by 1665, receiving commissions from local burghers and studio visits from foreign kings. He was not scrimping, scavenging for a used panel to paint on in 1685. Luttichuys, a generation older, was well-known in Amsterdam as a portraitist, and he died well-known in 1673, presumably content in the belief that this and his many other portraits would survive him.

In Judith Benhamou’s video, Milo mentions that this surreal composition is exceptional, but that they’d seen some things like it, or kind of similar to it. And I guess it’s true that overpainting is extremely common in the history of paintings: fig leaves get added, draperies get touched up, windows get painted out. But reading through the 1995 catalogue of the National Gallery’s 17th Century Dutch painting [pdf], overpainting is equated with chasing fashion or botched restoration; it’s a scourge to be obliterated on the way back to a painting’s earlier, more authentic state.

And that is very clearly not what Backhuysen was up to when he painted on top of Luttichuys’s head, turning it into a darkened storm cloud that hovers over four civilian boats. Was it perhaps a philosophical gesture? A reference to the giant on the frontispiece of Hobbes’ Leviathan [published in Latin in 1668]? Did it relate to the war in which William III of Orange set sail to seize the English throne from James, his father-in-law?

I guess I’m fine with not being able to know for sure. But I do wonder why we have to rely on the serendipity and close reading of a single gallery to discover incredible objects like this. I mean, TEFAF is good at surfacing rarities and lost masterpieces, but it still feels hermetic and almost random. What else are we missing?

About That Robert Irwin Documentary

I watched the Robert Irwin documentary, A Desert of Pure Feeling, and it is good. [It is currently on Kanopy for free, support your local public library.]

Some things stand out:

Irwin’s mystical-sounding development of his pursuit of perception was fascinating: posting up on Ibiza and not talking to anyone for eight months? wandering around the desert or whatever, painting dots for 16 hours/day, 7 days/wk? But he was not, in fact, alone in that pursuit. Some art world context would have been more helpful than repeating his refusal to allow his work to be photographed.

The Whitney installation was nice, but it felt somehow confusing, which is weird because there was even a real reinstallation of it, with footage and everything. The filmmakers did somehow manage to shoot other phenomenological aspects of other installations coherently.

Evelyn Hankins, who curated Irwin’s spectacular Hirshhorn retrospective, was thoughtful and present—but that show was somehow not, at all.

Which, wtf, the MCA San Diego’s masterpiece, 1° 2° 3° 4°, was done dirty here. Is it the ultimate “you had to be there” Irwin? Except for the Chinati building, which took up the last third of the film?

The dynamics of shooting and interviewing around Marfa and Chinati was weird. Marriane Stockebrand, the inviter, I guess, was everywhere, but Jennie Moore, the director who dragged that project across the finish line was airkissed in one crowd shot? Maybe that is #chinatiworldproblems, I guess I’ll demur. The weird caginess over whether he’d attend the 2016 ribboncutting was eerie, too; it made it sound like he died in production. [Spoiler: he stuck around for seven more years.]

For a documentary about perception and reproduction, it did shoot Irwin’s own dot paintings immaculately. But the shimmering moiré of halftone dots and pixels during pans across archival photos was hilariously distracting.

Seeing Arne Glimcher as a producer both makes sense and raises some flags, but how is that any different from anything the Glimchers have done all this time? It is what it is.

For such a singular thinker, who’d done so much work on his own mind and being, maybe give the film a title that reflects something he said, not just something he quoted?

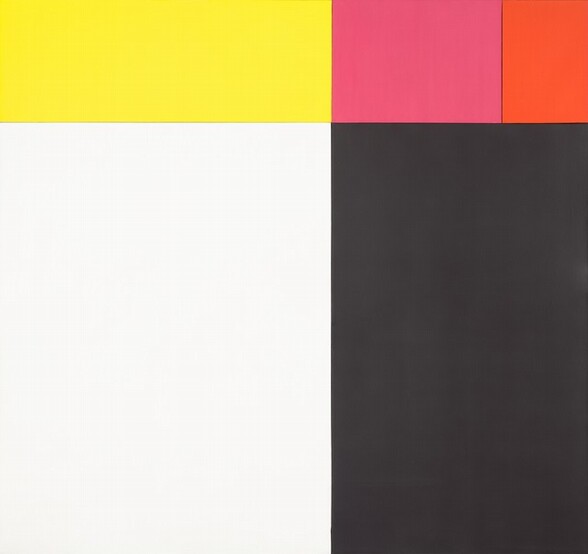

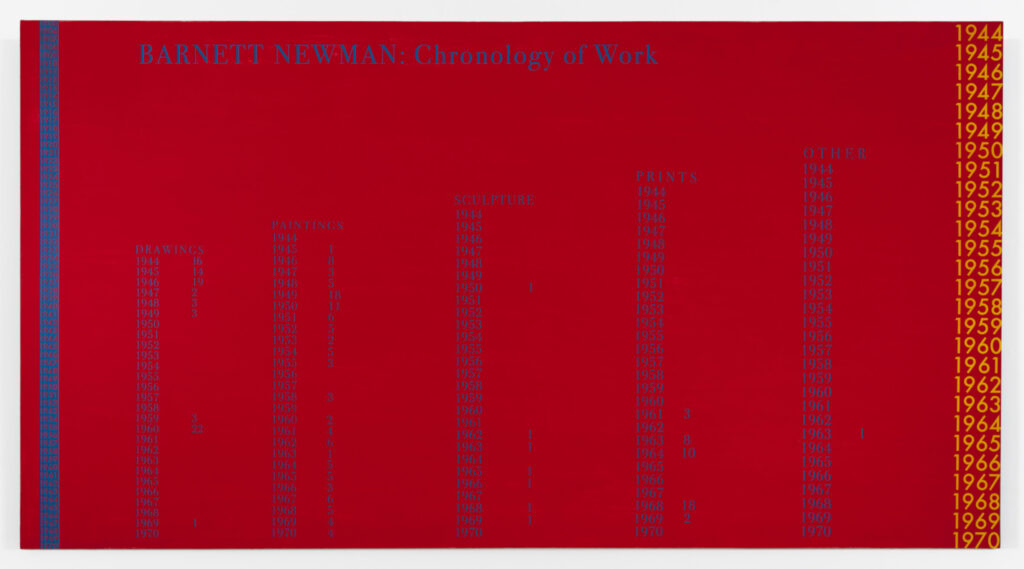

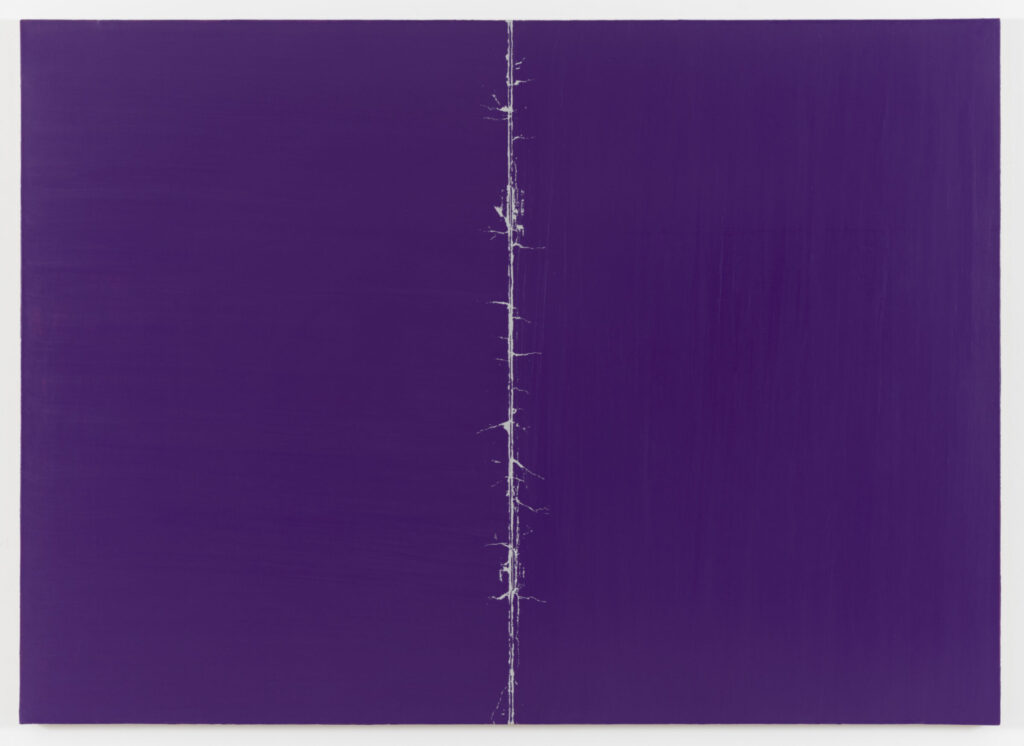

David Diao, Barnett Newman, and Books

Speaking of books derived from Barnett Newman paintings and paintings derived from Barnett Newman books, David Diao’s got both. Barnett Newman: Chronology of Work (Updated), 2010 [above], turns Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow & Blue into an infographic tallying Newman’s output, as recorded in the artist’s catalogue raisonné.

BN Spine (2), meanwhile, makes a zip from the cracked and worn spine of Diao’s copy of the 1966 Guggenheim catalogue for Newman’s Stations of the Cross. Diao worked as an installer on that show, and meeting Newman and his work had a foundational impact on Diao’s own project.

After Diao’s 2023 show at Greene Naftali, the gallery and Gregory P. Miller published a catalogue about his decades-long engagement with Newman’s work.

Previously, related: just look at the David Diao tag.

But also: Diao’s 2013 talk on Newman for Dia’s Artists on Artists series